Dividend investing is a great way for investors to see a steady stream of returns on their investments. Though the world of dividend investing can seem conservative and basic on the surface, there is a lot to know in the dividend world that can help investors create long term wealth.

Here are 40 things every dividend investor should know about dividend investing:

1. Dividends = Meaningful Portion of Stock Returns.

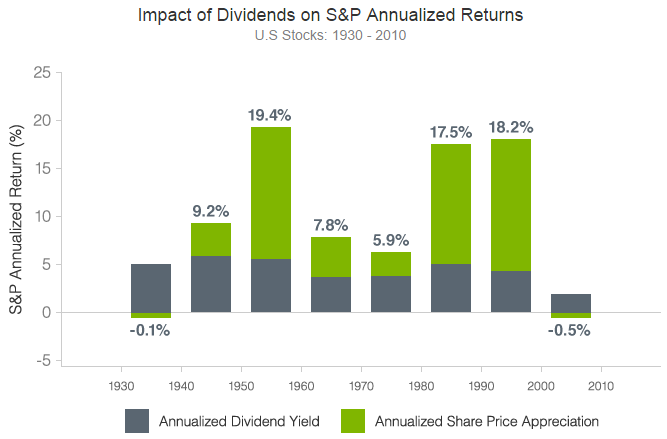

Going back over the past 80 years, dividends have accounted for more than 40% of the total returns of the S&P 500. It is important to note, though, that that has not been a steady or consistent ratio – capital gains tend to be considerably larger percentages during bull markets, while dividends make up much larger portions in weaker markets.

Consider the image below for a visual representation of just how much dividends have impacted the S&P 500’s returns over time:

2. Ex-Dividend Dates Are Key

It is very important for investors who want to hold dividend-paying stocks to pay attention to timing and certain key dates. The ex-dividend date refers to the first day after a dividend is declared (the declaration date) that the owner of a stock will not be entitled to receive the dividend. Prior to the open of trading on the ex-dividend date, the exchange will mark down the price of the stock by the amount of the dividend. Those investors wishing to receive a declared dividend must buy the shares before the ex-dividend date to receive that dividend.

For up-to-date info on ex-dividends, check out our Ex-Dividend Tool.

3. Dividends Come in Various Frequencies

There are really no hard and fast rules (in the United States, at least), regarding when a company can pay dividends. Tradition (and expectation) still carries a great deal of weight, though, and it has become the established norm for most regular corporations to pay dividends on a quarterly basis. Many well-known dividend-paying companies like Coca-Cola (KO ) and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ ) pay dividends on a quarterly basis.

What is commonplace in the United States is not necessarily so elsewhere. In many countries, dividends are declared and paid once or twice a year. Chinese oil and gas giant Petrochina (PTR ) and British spirits giant Diageo (DEO ) pay twice a year, while Novartis (NVS ) and Siemens (SI ) each pay annual dividends.

Although it is the norm in North America for companies to pay dividends quarterly, some companies do pay monthly. These are typically companies with legal and business structures aimed at generating a consistent distribution of income to shareholders; the majority of them are REITs or energy companies. Likewise, many ETFs (particularly those that invest heavily in income-generating assets like bonds) pay dividends on a monthly basis.

See our complete list of Monthly Dividend Stocks

4. ADR Yields Can Be Confusing and Inconsistent

American Depository Receipts (or ADRs) offer investors a chance to invest in foreign companies. While these are basically simple instruments that trade like any other stock, they can be a little confusing and inconsistent when it comes to dividends and the reported yields on financial information sites.

Be sure to see our complete list of Foreign Dividend Stocks.

Some of the trouble comes from how these sites calculate yields. Some sites will take the most recently-paid dividend and multiply it by the number of times the company pays a dividend in a year (typically one or two for most foreign companies). Other sites will simply use the total dividends paid over the past twelve months. Likewise, many sites tend to be slow or inconsistent in incorporating announced changes to, or declarations of, dividends.

Currency can also have a meaningful impact on ADR yields. ADR dividends are typically declared in the operating currency for the company, but paid to the ADR holders in dollars. How and when a financial site applies the exchange rate to this conversion can have a meaningful impact on the reported yield.

It is also important to note that the reported yield of an ADR is not necessarily what an investor will receive. Many countries require that companies paying dividends to foreign shareholders withhold taxes, reducing the dividend. ADR custodians are also allowed to deduct custody fees (basically, the expenses they charge for managing and maintaining the ADR) from the dividend, further reducing the yield. Both foreign withheld taxes and custody fees are typically deductible for individual tax purposes (at least when held in taxable accounts).

5. Dividends Are Not Capital Gains or Income

Dividend income is unusual in that it has typically already been taxed (corporations pay taxes on the income that they then use to pay dividends), but that does not shield it from additional taxation. Prior to the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (the “Bush tax cuts”), stock dividends were generally taxed at the same rate as an investor’s ordinary income.

| Ordinary Income Tax Rate | Ordinary Dividend Tax Rate | Qualified Dividend Tax Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 10% | 0% |

| 15% | 15% | 0% |

| 25% | 25% | 15% |

| 28% | 28% | 15% |

| 33% | 33% | 15% |

| 35% | 35% | 15% |

| 39.60% | 39.60% | 20% |

Learn more about Qualified Dividend Tax Rates.

With these tax cuts, a new category of “qualified dividends” was created, and those that qualified (which would include most regular corporate dividend payments) were taxed at a new, lower rate. From 2003 to 2007, qualified dividends were taxed at either 15% or 5% (if the individual’s tax bracket was 10% or 15%). From 2008 to 2012, the tax rates for qualified dividends were 15% or 0% (again for investors in the 10% or 15% brackets).

6. Payout Ratios Above 100% Are a Red Flag

Dividends are supposed to be a mechanism by which companies share their financial success with the shareholders. While dividends do not, strictly speaking, have to come from earnings it is not sustainable for a company to pay out more than it earns.

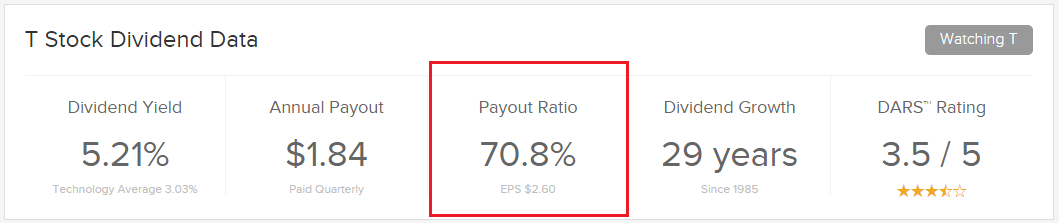

Accordingly, it is important for investors to monitor a company’s payout ratio. The payout ratio is simply the ratio of dividends in a specified period (typically the last twelve months) divided by the company’s reported earnings over the same period. For simplicity’s sake, most dividend payout ratios use the per-share dividend as the numerator and the earnings per share (EPS) as the denominator.

If a company has $1 per share in earnings and pays a $0.70 per share dividend, the payout ratio is 70%. Likewise, if the dividend were $0.10 the payout ratio would be 10%.

If the same company paid a dividend of $1.20 per share, the payout ratio would be 120% and investors would do well to ask how that company could hope to continue a dividend in excess of its earnings. Companies do try to maintain consistent (or rising) dividends, even in industries where year-to-year financial performance can vary. Consequently, not all companies with a dividend payout ratio above 100% are paying an unsustainable dividend, but no company can indefinitely pay out more in dividends than it earns.

You can see the payout ratio of a company right next to where the annual payout is listed on all Dividend.com ticker pages; take for example AT&T (T ).

It is also worth noting, though, that “earnings” (and earnings per share) are a byproduct of accounting and not strictly real. Companies actually pay dividends out of the cash flow they generate, though it is not common to see payout ratios calculated on the basis of operating or free cash flow.

Learn everything you need to know about the payout ratio in The Truth About Dividend Payout Ratio.

7. Effective Yield Is Based on Your Adjusted Cost Basis

One of the underappreciated ways to evaluate dividends is in the context of the investor’s own historical cost basis in the stock. “Effective yield” is a concept with multiple definitions in investing, but one definition includes evaluating dividend yield on the basis of an investor’s own cost basis. This analysis helps to cover the deficiency of information offered by current yield.

Consider the following – a stock currently trades at $50 and pays a $2 dividend, meaning that the stock has a current yield of 4%. But if an investor bought that stock years before (and the stock price has increased since then), it’s not an accurate reflection of the yield on the investment. If the investor bought the stock at $35, the current yield on that cost basis (what we’re calling the effective yield here), is actually 5.7% ($2 divided by $35).

8. Current Yield Is Based on Different Calculations

Current yield is a relatively common concept in dividend investing. The current yield is simply the dividends paid per share divided by the price per share. If a company pays a $1 per share dividend and the stock price is $100, the current yield is 1%.

Yet not all sources calculate and report current yield the same way. While most sites report yield on the basis of four times the most recently paid or declared dividend, some pay on the basis of the dividends paid over the past 12 months.

Consider the following to see the difference – if the company in the prior example announced that it was increasing its dividend by 15% (to $1.15 per share), some sites would report the yield as 1.2% (1.115% rounded up), while some would continue to report 1% until the first payment at the higher rate, at which point the yield would move up to 1.04% (three quarters of the old $0.25/qtr dividend + one quarter of the new $0.2875 dividend).

If you’re looking for lucrative income investing opportunities, be sure to check out our list of High Yield Stocks.

9. Cumulative Dividends: Declared, Not Yet Paid

In some cases, corporations issue preferred stock that carries a right whereby any unpaid preferred dividends accumulate and must be fully paid before certain other payments (like common stock dividends) can be made. Unpaid dividends accumulate and this type of preferred stock is called “cumulative preferred.”

This is not to be confused with a stock that is trading “cum-dividend,” which refers to a stock where a dividend has been declared and current buyers are entitled to that dividend (cum-dividend means “with dividend”). Stocks cease to trade cum-dividend on their ex-dividend date, which is listed on Dividend.com ticker pages (see table above).

10. Dividend Aristocrats: Exclusive Club

Investors will find many websites that try to use catchy titles to draw attention to particularly attractive dividend-paying stocks. One title worth looking out for is “dividend aristocrat”. Standard & Poors (“S&P”) defines a dividend aristocrat as a company that has increased its dividend for 25 straight years, excluding special dividends.

Be sure to see our complete list of 25-Year Dividend Increasing Stocks.

11. Value Stocks with Dividend Discount Models (DDM)

Dividend discount models work on the theory that the only real value to a shareholder is the dividend stream that a company produces (academic theory holds that capital gains and variability in share prices are unpredictable and simply the byproduct of investors adjusting their expectations for a company’s future stream of dividends). Consequently, a dividend discount model attempts to project these dividends and discount them to a net present value per share that represents a fair value for the shares.

Arguably the most accurate way to run such a model is to project a company’s dividends for as many years as possible, calculate a terminal growth rate, and then discount that back by the appropriate discount rate. That discount rate should be the cost of the company’s equity, whether determined through the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) or some other method.

Some investors try to use a more simplified version of the model, like the one listed below:

Stock Value = D1 / R – G

This version has the investor use next year’s anticipated dividend (D1), divided by the cost of equity® minus the estimated perpetual growth rate of the dividend (G). As an example, if a company is projected to pay $1 per share in dividends next year, the growth rate is projected to be 5%, and the cost of equity is estimated to be 8%, then the fair value for the stock is $33.33.

Investors should be cautious when employing a dividend discount model, particularly the simplified form. The model assumes that a firm’s cost of equity never changes, that the dividend growth rate never changes, and that the dividend growth rate is less than the cost of the firm’s equity.

Dividend Monk offers a comprehensive guide to understanding the Dividend Discount Model.

What’s more, while the model is quite simple and requires very few inputs, the end result is very sensitive to the inputs – a small difference in the estimated growth rate or discount rate can result in large differences in the implied value of the equity (in the above example, changing the growth rate estimate by only 5% (to 5.25%) changes the fair value by 9% (to $36.36).

12. The Power of Re-Investing Dividends

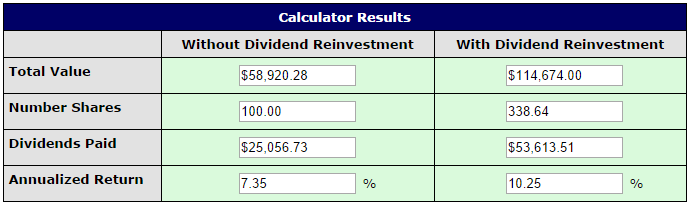

Reinvesting dividends, particularly those paid by companies with a history of increasing their dividend over time, can be a powerful avenue to increasing total wealth over time. Although investors have to pay taxes on reinvested dividends in taxable accounts, that money nevertheless “stays active” in the stock and accumulates value.

The following table illustrates the power of reinvested dividends using the Dividend Reinvestment Calculator. In the example below, let’s assume you purchase 100 shares of a stock trading at $100 per share ($10,000 total investment) and plan to hold it for the next 25 years. At the time of purchase, the security pays a $5 dividend annually, or 5% yield, and its share price and dividend are both expected to grow at a rate of 5% annually.

After 25 years, your $10,000 initial investment would have grown to nearly $59,000 without any reinvestment; by comparison, that same amount could have grown to nearly $115,000 had you regularly reinvested your dividends.

13. Basics of DRIPs (Dividend Reinvestment Plans)

Dividend Reinvestment Plans are investment plans offered directly by dividend-paying companies. When a shareholder enrolls in a DRIP, they no longer receive a company’s quarterly dividends as cash, but rather the amount is used to directly purchase more shares from the company.

Although the investor is still obligated to pay taxes on the dividend amounts, the investor forgoes brokerage commissions to buy those shares and can buy fractional shares. In some cases, but not all, the sponsoring company may give a discount to the share price on these purchases. In many cases, an investor may choose to receive a certain percentage or amount of the dividend in cash, while having the remainder reinvested in shares.

There may be some downsides to certain reinvestment plans however, so be sure to read our guide Everything Investors Need to Know About DRIPs.

14. Dividend Capture Strategies

Although investing in dividend-paying stocks and collecting those quarterly payments is considered consummately conservative equity investing, there are much more aggressive ways to play dividend-paying stocks, including dividend capture strategies.

In essence, dividend capture strategies aim to profit from the fact that stocks do not always trade in strictly logical or formulaic ways around the dividend dates. For instance, while a stock is marked down before trading begins on the ex-dividend date by the amount of the dividend, the stock does not necessarily maintain that adjustment when actual trading begins (or ends) that day. Likewise, the desire to reap the benefit of the upcoming dividend often spurs interest in the stock ahead of the ex-dividend date, leading to short periods of out-performance.

In its simplest form, dividend capture can involve tracking those stocks that, for whatever reason, do not generally trade down by the expected amount on the ex-dividend date. Investors may notice that although a given company pays a $1 dividend, the stock only declines by an average of $0.50 on the ex-dividend date. That being the case, an investor can buy the stock on the day prior to ex-dividend (say, for $100), sell it on the ex-dividend date (say for $99.50), and the collect the $1 dividend a few weeks later – leading to a total return of $0.50 per share on the trade (losing $0.50 on the stock, but gaining the $1 dividend).

Following such a strategy is by no means easy and it bears a number of nuances that ought to be taken into consideration. For anyone looking to take advantage of this approach, be sure to first read our Dividend Capture Strategy Guide for a more thorough understanding of the risks involved.

15. Companies Can’t Fake Dividends

Some investors prefer dividend-paying stocks because dividends are real and trackable. A company’s reported net income or earnings per share (EPS) is largely a product of accounting, and may have little or nothing to do with a company’s actual financial health. As a result, devious executives and skilled accountants can make even a terrible company look healthy through the lens of earnings and reported income.

Dividends are different. Dividends either appear in shareholders’ accounts or they don’t – and if they don’t, there are no accounting tricks that explain it. Dividends don’t necessarily have to be paid out of income, but paying dividends creates a paper trail of cash that is much harder to manipulate.

This is not to say that a company’s dividends are an accurate representation of a company’s financial health or liquidity. Companies can, and have, paid dividends with borrowed money or sources of funds other than operating cash flow. Learn more about The Biggest Dividend Stock Disasters of all Time.

16. There’s No Free Lunch

Dividends are basically a mechanism for companies to share their financial success with long-term shareholders, and short-term investors cannot simply buy and sell around dividend dates to reap risk-free profit. On the ex-dividend date (the date on and after which new buyers will not be entitled to the dividend), the price of the stock is marked down by the amount of the declared dividend. While shares do not always fully maintain this adjusted value (see our section on “Dividend Capture” above), trading shares around dividend dates is not a simple alpha-generating strategy.

While it may be true that there’s no free lunch on Wall Street, there are still more than a handful ways investors can make (and keep) more money over the long-haul.

17. Dividends May Foreshadow Lower Growth

Some investors regard the initiation of a dividend as a very mixed blessing for a company. Generally speaking, companies should retain earnings when management can reinvest that capital into projects that are expected to generate a return in excess of the firm’s cost of capital. If a company cannot identify enough projects that meet that minimum return, though, the shareholder-friendly move to make is to return that capital to shareholders in the form of dividends (and/or share buybacks).

When companies begin a dividend, and particularly when the company is a tech company like Microsoft (MSFT ), Cisco (CSCO ) or Apple (AAPL ), some investors regard this as proof that the company can no longer find attractive avenues to growth.

See 10 Big-Tech Stocks That Pay a Dividend

Although this analysis contains an element of truth, it is in many cases exaggerated. Spending retained earnings on R&D does not guarantee future results, and there is not always (or even often) a direct relationship between the money invested in new a project and its future returns. Take the case of the Apple iPhone – Apple reportedly spent about $150 million over 30 months to develop the iPhone, a product that has generated billions in profits.

It does not automatically follow, then, that the next project is going to require billions of dollars to develop, or that investing billions into development will somehow “guarantee” a multibillion dollar product. Consequently, many innovative companies find that they simply generate more cash than they can effectively redeploy in their business. That makes returning that cash to shareholders more desirable than wasting it on inefficient or unfocused R&D or ill-considered (and over-priced) acquisitions.

It is typically true that a company’s fastest growth days are behind by the time it initiates a dividend. As many dividend-paying companies like Abbott Labs (ABT ), McDonald’s (MCD ), and IBM (IBM ) have amply proven, though, the initiation of a dividend does not preclude further growth for a company.

18. Dividends Can Protect from Inflation

Owning dividend-paying stocks, particularly those that increase the dividend regularly, can be a better hedge against inflation than bonds. The problem with bonds (excluding floating-rate bonds) is that they pay fixed income streams over the life of the bond – the dividend payments in Year 20 are the same as Year 1. In periods of inflation, that means each successive interest payment is worth less in terms of purchasing power, and it also means that the purchasing power of the principal amount of the bond (which may not mature in 10, 20, or 30 years) could erode substantially as well.

Learn more about How Dividend Stocks Can Protect Against Inflation.

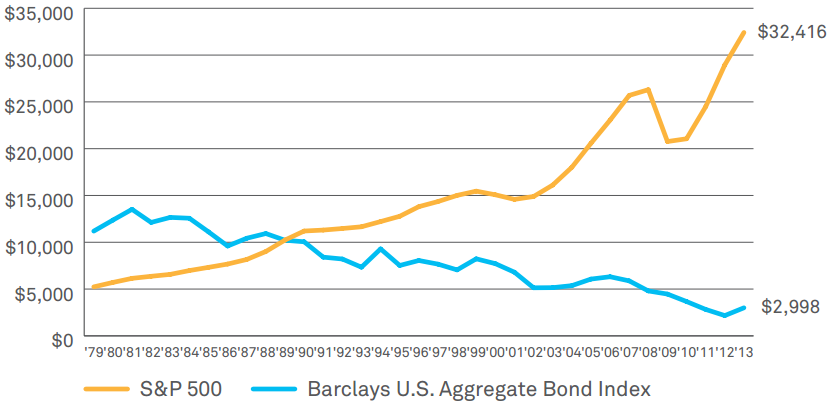

Consider the chart below which illustrates how your annual dividend income from a $100,000 investment would have changed over time from 1980 through 2013, comparing what you would have earned had you invested in the S&P 500 Index versus the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index:

The dividend income earned from the S&P 500 investment would have grown from $5,234 to a whopping $32,416 over time, compared to that of the bond investment which has seen a steady decline in annual income.

With a dividend-paying stock, investors do not lose to inflation if the dividend grows as fast as (or faster than) the inflation rate. According to data collected by Robert Schiller at Yale University, dividends from the S&P 500 have grown at an annual rate of 4.2% since 1912, while the consumer price index (the most commonly accepted proxy for inflation) has risen by 3.3%.

19. Non-Cash Dividends

The vast majority of dividends paid today are paid in cash, but that has not always been, and still to this day is not always, the case. Dividends can be paid out in virtually anything of value, and companies have paid dividends in their own stock, other companies’ stock and with physical goods.

Although it’s uncommon now, many companies used to “pay” regular stock dividends whereby shareholders would get a certain number of shares for every share they already owned (typically a small fraction like one share for every 20). The reason pay is in quotation marks is that stock dividends really aren’t dividends in the traditional sense – they are stock splits and the share price adjusts accordingly, meaning that shareholders are financially no better off post-stock dividend.

Some companies have used the dividend mechanism to spin off or divest holdings in other public companies. Many companies treat these as special or one-time dividends, not as regularly quarterly payments to shareholders. In these cases, shareholders receive actual shares of stock (or warrants or rights) to the other company as the dividend in proportion to their share ownership of the issuing company.

In some rare cases, companies have also used physical goods as dividends – Wrigley’s gave shareholders packs of gum every year, and other companies (particularly in entertainment and dining businesses) would give coupons or vouchers to shareholders. Although these have usually been regarded by the issuing companies as gifts or perks of share ownership, they are technically dividends.

20. Some Tech Companies Can Pay Attractive Dividends

Tech companies are not traditionally major dividend payers, but that trend has changed as tech companies mature and accumulate more cash than they can effectively redeploy in growing the business.

IBM (IBM ) has paid a dividend since the late 1960s, while Texas Instruments (TXN ) has paid one since the early 1970s. Hewlett-Packard (HPQ ) began paying a dividend in the early 1990s, and many of the tech stars of the 1980s and 1990s, including Microsoft (MSFT ), Cisco (CSCO ), Oracle (ORCL ) and Intel (INTC) have initiated dividends over the past decade.

21. AT&T Is the U.S. Dividend King

Though Apple (AAPL ) is by far the largest U.S. stock by market cap, it’s far from the top dividend payer. That title belongs to AT&T (T ), which paid out $9.7 billion in dividends last year. That means AT&T pays out about $18,000 in dividends to its shareholders each minute.

22. Dividends Can (and Do) Get Cut

Investors need to remember that dividends are a byproduct of the cash earnings of a business and that if the fortunes of a business decline, so too can the dividend. Companies as varied as General Motors, Kodak, and Woolworth all once paid robust dividends, until their fortunes changed severely (all three companies went bankrupt, and Woolworth disappeared from the business landscape years ago).

It doesn’t even take total devastation to hurt a dividend. Virtually every U.S. bank that participated in the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), and almost all U.S. banks were part of the program, was required to cut its dividend.

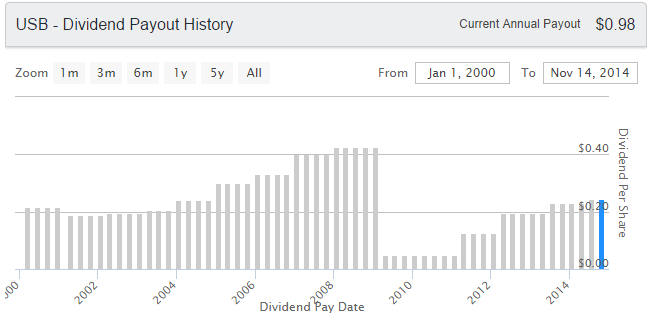

Many reliable dividend-paying banks like U.S. Bancorp (USB ) cut their dividends, and in some cases cut them dramatically; consider the chart below and take note of the steep drop in the distribution seen after the 2008 financial crisis.

23. Not All Dividend Payers Are “Stocks”

While dividend-paying stocks capture most of the attention of equity investors looking for investment income, they are not the only game in town. Many other financial instruments that trade like stocks offer investment income to their owners.

Exchange traded funds and exchange traded notes (ETNs) are often designed to replicate a stock market index, and many of these stocks pay dividends. Likewise, many ETFs and ETNs invest in income-generating securities like bonds. Consequently, many of these ETFs and ETNs pass on these dividends to shareholders.

Master limited partnerships are businesses organized under special rules that allow them to avoid corporate taxation and pass on a substantial portion of their income to owners. MLPs are not technically corporations, they do not issue shares (a share of an MLP is typically called a “unit”), and they do not pay dividends (they pay “distributions”), but in many respects owning an MLP is similar to owning a dividend-paying stock. Investors should note that the tax treatment of MLP distributions is different than that for common stock dividends.

Real estate investment trusts are special types of businesses organized in a way to pass on substantial corporate earnings to unit holders. As the name suggests, these businesses have to be engaged in real estate operations in some way (owning/operating buildings or land, owning/trading mortgage bonds, etc.), and their earnings are free of corporate taxes so long as a legally-mandated minimum percentage of earnings are distributed to shareholders.

24. Dividend Tax Rates Have Varied Historically

Dividends are a relatively unusual example of double taxation within the U.S. tax system. A corporation generally pays dividends out of income – income that is taxed by the U.S. government. Those dividends are then once again subject to taxation is held in a taxable brokerage account.

It has been the case over history, then, that dividend tax rates have varied and not always in lock-step with ordinary income tax rates or capital gains tax rates. See table below for reference:

| Time Period | Tax Rate on Dividends |

|---|---|

| 1913-1936 | Exempt |

| 1936-1939 | Individuals income tax rate (Max 79%) |

| 1939-1953 | Exempt |

| 1954-1985 | Individuals income tax rate (Max 90%) |

| 1985-2003 | Individuals income tax rate (Max 28-50%) |

| 2003-Present | 15% |

Read more about The History of Dividend Tax Rates.

25. MLPs Can Offer Attractive Dividends

Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) are a special type of limited partnership (a way of organizing/creating a business) that can trade on public stock exchanges. MLPs must generate the bulk (90%+) of their income from what the IRS deems to be “qualifying sources,” which typically means activities related to the production, processing, transportation and distribution of energy (oil, natural gas, various distillates, coal, etc.). As partnerships, MLPs do not pay income tax and can pass on pro-rated shares of their depreciation to unit holders.

The tax treatment of MLP distributions can be quite complex and will vary from investor to investor. To better understand some of these nuances, consider our guide Everything Dividend Investors Need to Know About MLPs.

26. Certain Sectors Are Known for Stable Dividends

Within the dividend investing world, certain sectors have earned a reputation as reliable dividend-payers. In particular, utilities and telecoms are famous go-to sectors for dividend-paying companies. Prior to the housing market crash in the United States and the result recession, banks too were often seen as reliable dividend payers.

Sectors known for being reliable dividend-payers tend to share certain characteristics; to learn more about these, read our guide to Dividend-Friendly Industries.

27. Tech Companies Are Starting to Boost Dividends

Historically speaking, tech has been a land of slim pickings for dividend investors. As tech companies founded in the 1970s and 1980s have matured, though, suddenly investors have a much more promising array of dividend-paying investment opportunities in the tech world.

Dividend-paying tech stocks may also offer more growth potential than dividend investors are commonly used to seeing. While it is true that many investors regard the initiation of a dividend as a sign that a company’s best growth days are behind it (particularly in tech), that does not mean that a company will never grow again. This could be particularly true in the case of technology, where new product development does not typically require a proportionate reinvestment of capital (it typically takes less than $1 of reinvested capital in technology to generate an incremental dollar of capital).

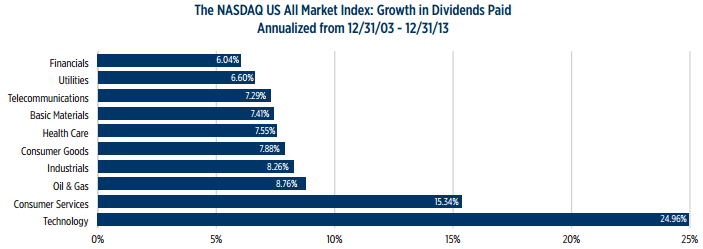

Consider the image below which showcases the growth in dividends paid by every sector since 2004:

Tech companies can, and in many cases do, offer above-average dividend growth potential. Companies typically initiate dividends at low levels relative to their payout capability, giving the leeway these companies have to raise the payout ratio in the future. What’s more, if tech companies can continue to grow faster than the market, it increases the probability of above-average dividend increases.

28. Don’t Be Fooled by Capital Gains Distributions

Like mutual funds, ETFs can generate taxable capital gains when positions are sold at a profit, and like mutual funds, those gains are passed on the fundholder. While most ETFs are highly tax-efficient and run themselves in such a way as to minimize capital gains distributions, it is nevertheless true that ETFs will periodically distribute these taxable capital gains to shareholders.

Learn more about When an ETF Distribution Isn’t a Dividend.

These distributions may look like dividends (and can generally be reinvested) and some financial news sites may erroneously include them in reported yields, but they are not dividends – they are capital gains and taxed at an investor’s capital gains rate.

29. The Basics of One-Time Distributions

While most U.S. companies that pay dividends strive to do so on a consistent schedule, some companies do pay special one-time dividends. These payments can serve many purposes; in some cases, it is a way for a company to share the proceeds of a major asset sale. In other cases, it may be part of a recapitalization of the business or a way of disgorging accumulated cash without effectively obligating the company to a higher ongoing dividend payout.

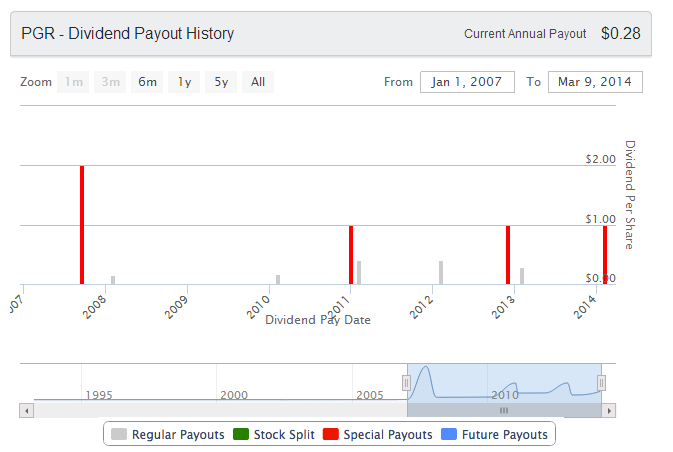

For example, consider the special dividend paid out by Progressive Corp (PGR ) over the years:

To learn more about this topic, see 8 Examples of Special Dividends.

In some cases, companies can categorize these special one-time payouts as a “return of capital.” In doing so, the distributions become tax-free to the recipients.

30. Companies Can Issue Stock Dividends

Not all dividends have to be paid in cash. Companies can pay dividends with additional shares of stock (stock dividends). When companies do this, they are effectively splitting the stock and the stock’s price adjusts accordingly.

31. There’s a Long History of Dividends

The concept of dividends goes back so far that the question of the first company to pay a dividend is very much an open question. A French joint stock company, Société des Moulins du Bazacle, may well have been the first (the company was formed in 1250), and other companies formed in the 16th century and early 17th century like Muscovy Company and East India Company paid dividends to their shareholders.

The Hudson Bay Company was the first North American commercial corporation, and most likely the first to have paid a dividend. That first dividend (paid 14 years after the company’s formation in 1670) was a whopper too – 50% of the par value of the stock.

Looking for historical dividend stock data? Use our ticker pages to download important distribution data to aid your analysis.

32. There Are Many Dividend-Paying Stocks at Home

As of the end of September, 2014, there were reportedly 2,940 stocks that paid a dividend trading on U.S. exchanges. Additionally, the number of dividend-paying members of the S&P 500 Index stands at over 400, which is the highest level since 1999.

Dividend.com is a great resource to keep track of the definitive information for the vast amount of dividend paying equities; the Stock Screener tool makes it easier to find the security that may be right for you.

33. Buffett says “Always Reinvest Dividends!”

Famed investor Warren Buffett has come out in the past in favor of reinvesting dividends. Investors should note, though, that Buffett generally does not follow his own advice in this regard. While Buffett will add to his stock positions from time to time, he does not reinvest his dividends as a matter of course; Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B)has owned the same number of Coca-Cola (KO ) shares for more than 15 years.

Be sure to see our Unofficial History of Warren Buffett for more insights on his personal life as well as his success in the investing world.

34. Dividend Increases: Leading Indicator

Analysts and investors often regard announced dividend increases as positive predictors of future corporate performance. One of the biggest reasons behind this is a seemingly unspoken agreement that dividends are supposed to go up or remain steady, but not decline; companies that announce lower dividends are typically perceived as weak/vulnerable, and investors often shun or sell off the stock.

Be sure to see our analysis on S&P 500 Companies that Can Afford to Start Paying a Dividend.

Consequently, corporate boards are typically hesitant to establish dividends that they are not confident they can maintain; if a company announces a higher dividend, it often signals to the market that management believes operating conditions have improved and are likely to stay at a higher level for the future.

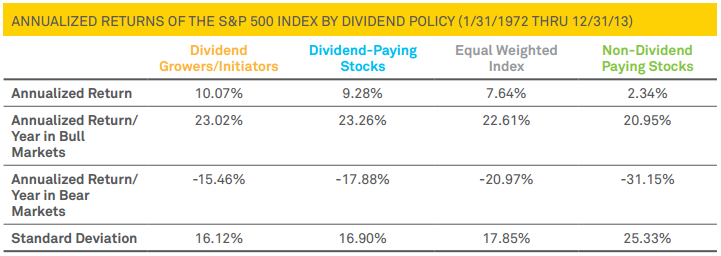

35. Volatility of Dividend-Paying S&P 500 Stocks vs. Non-Dividend-Paying Stocks.

An analysis by Ned Davis Research showed that, through December of 2013, the standard deviation of returns for dividend-paying members of the S&P 500 was 16.90%, while the standard deviation for non-dividend-paying members was 25.33%.

The data also reveals that dividend-paying stocks tend to perform better during bull markets as well as bear markets compared to their non-dividend-paying counterparts.

36. REITs Can Deliver Big Distributions (and Big Risk)

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) can be some of the largest dividend-payers in the stock market, due largely to the preferential tax treatment a company receives if it elects to organize as a REIT. Provided that a REIT distributes a certain percentage of its taxable income (presently 90%) to shareholders, the company’s income is not taxed by the government.

While at least 75% of assets must be invested in real estate and 75% of gross revenue must come from rents or mortgage interest, there is some flexibility here, and investors can find companies like timberland operators organized as REITs.

To learn more about this breed of dividend-payers, be sure to read our Definitive Guide to REITs.

The favorable tax treatment granted to REITs allows for larger distributions to shareholders, but these investments can be quite risky. Although real estate has a strong history of performance relative to inflation, many of the businesses owned/operated by REITs are economically sensitive – when the economy weakens, shopping mall traffic declines, office space vacancies increase, and so on. What’s more, most REITs rely heavily upon debt financing and the combination of lower rents/interest income and persistent interest payments during recessions can put these companies into financial duress.

37. Royalty Trusts Can Be Attractive for Dividend Investors

Like REITs and MLPs, royalty trusts are created with the intention of shielding a business entity’s earnings from taxes and passing the overwhelming majority of those earnings on to the shareholders as dividends (or, more technically, distributions).

The distributions of royalty trusts are usually generated from businesses related to oil/gas or mining. In most cases, a U.S. royalty trust will own a particular asset and lease that asset to operators who produce the oil or other resource and pay a percentage back to the trust. The trust uses that cash flow to pay its operating expenses and passes the remainder on to shareholders. The existence of the mineral asset typically assures some level of payout, though the dividend can vary considerably over time as the value of the commodity changes.

38. Good Dividend Stocks Have More Than Just Good Yields

Successful dividend stock investing is more than just selecting those stocks with the most impressive yields. Dividend.com has created a system called DARS™ to reflect and evaluate these other critical factors.

- Relative Strength – Relative strength is a well-established technical analysis concept that argues that strong stocks tend to continue outperforming, while weak stocks tend to continue underperforming. In DARS™, relative strength assesses where a stock is relative to its 50-day and 200-day moving averages to assess whether it is in an uptrend or not.

- Overall Yield Attractiveness – This is a subjective measure that evaluates both the size of a company’s dividend yield and its sustainability. Very high dividend yields tend to be quite unsustainable and the stocks tend to have above-average risks, while stocks with very low dividend yields are generally not worthwhile for long-term dividend investors.

- Dividend Reliability – While there are numerous examples of reliable dividend payers that hit hard times, the reality is that the best predictor of a company’s ability to continue paying dividends is the number of years it has done so. Accordingly, the DARS™ Dividend Reliability rating reflects not only the number of years that the company has paid dividends, but a subjective evaluation of how likely it is that current payout levels can continue.

- Dividend Uptrend – The DARS™ Dividend Uptrend factor reflects the company’s history of increasing its dividend, as well as a subjective evaluation as to the likelihood of future payout increases.

- Earnings Growth – Dividends are ultimately dependent upon income and income growth. Accordingly, DARS™ tracks a company’s a company’s projected earnings growth to ascertain and rate its ability and likelihood to continue paying (and/or raising) its dividend.

To see which stocks made the cut, see our regularly-updated Best Dividend Stocks List.

39. Dividends Once Dominated Investing

It may seem hard to believe, but dividends were once the preeminent consideration for equity investors. In fact, prior to the Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, it was routinely the case that stocks were expected to yield more than bonds to compensate investors for the additional risk that equities carried. While the concept of capital appreciation was understood then, investing on the basis of expected capital appreciation was considered as something roughly equivalent to speculative investing and active trading today.

40. Dividends: Antidote to Low Rates

Dividend-paying stocks can also offer investors an antidote to low interest rate environments. Since the Great Recession, interest rates have been stuck at historically low levels, making it very difficult for risk-averse investors to find attractive yields. Although dividend-paying stocks are not as safe as government bonds, they do offer better after-tax yields.

While interest rates are determined in part by central bank policy, corporate dividend policy is more independent and corporate dividends can increase even while central banks are cutting rates, which reduces available yields on bonds.

The Bottom Line

Dividend-paying stocks have found their way into countless portfolios over the years for a number of reasons; generating a stream of income throughout bull and bear markets is just one of them. If you’re considering an investment, be sure to take a good look under the hood and uncover any nuances before making an allocation. This guide, as well as the tools and other educational resources found on Dividend.com, should serve as a great starting point for those looking to beef up their portfolio’s yield.

Be sure to follow us @Dividenddotcom.