The corporate tax rate in the U.S., which currently sits at 35%, has long been a point of contention among major businesses. With one of the highest corporate tax rates in the world, the U.S. has tried to fill its coffers through corporate revenues, but in reality, most companies only pay about half of that 35% rate (and a handful have paid zero taxes), after intense lobbying has led to the creation of numerous loopholes and write-offs.

Even still, a number of companies have moved their headquarters overseas in recent years in order to capture the more favorable tax rates of foreign nations. The process is called an inversion and it is perfectly legal, but it is finally starting to see some backlash.

Explaining Corporate Inversions

In the simplest form, an inversion involves a company re-incorporating in a different country. It used to be that all a firm had to do was set up shop in the Cayman Islands or another low taxing country, and it was off and running. But legislation over the years to try and curtail this practice has made the process much more difficult. One law states that a firm must have 25% of assets, income, and employees where it is legally domiciled; this has in turn led to a merger/acquisition frenzy.

Be sure to also read How to Bankrupt a Multi-Billion Company: General Motors.

In most cases of inversions today, a large corporation will acquire or merge with a smaller one based abroad where tax rates are far lower (Ireland’s 12.5% rate has been a particularly big draw). The corporation will then move its headquarters overseas and re-incorporate (among some other things) to enjoy lower tax rates.

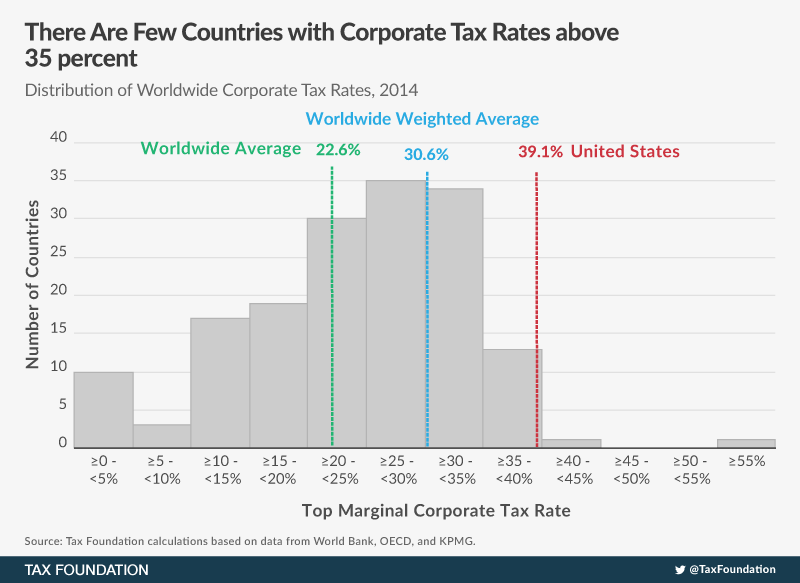

The table below illustrates why so many corporations have felt the need to escape taxes; in short, the U.S. corporate tax rate is well-above the worldwide average:

As time goes on, it has become more obvious that firms are simply moving as a tax shelter, which has brought about an onslaught of negative press. Leaving the U.S. simply so that you can have lower taxes often means lost jobs at home and sends a bad message to the general public. These days, an inversion has become a bit dicey from a PR standpoint, so many companies try to make it about a “strategic change” rather than outright admitting it is a move for tax purposes.

Below are just a few of the most recent examples of corporate inversions:

AbbVie Inc. (ABBV ) Buys Shire (SHPG)

In July of 2014, AbbVie purchased the Ireland-based biopharmaceutical company for a whopping $54 billion, making it the largest inversion to date. Abbvie will lower its effective tax rate to 13% by 2016 from its 22.6% effective rate in 2013.

Medtronic, Inc. (MDT ) Buys Covidien (COV)

In June of 2014, Medtronic purchased Covidien (another Ireland-based company) for $42.9 billion. This allowed Medtronic to lower its effective tax rate from 18.4% in 2013 to 12.5%.

Pfizer (PFE ) Rejected by AstraZeneca (AZN )

Pfizer made three major offers to take over rival AstraZeneca, all of which were denied for “undervaluing” the company. AstraZeneca is based in London, which would have allowed the company to lower its tax rate to about 21%.

Blocking Inversions

The Obama administration has begun cracking down on inversions and has made an example of Walgreens (WBA ) in order to do so. President Obama has been clear on his stance against inversions, calling them “unpatriotic” and vowing to find ways to discourage companies from taking such actions. While it is not immediately clear what that would mean, the pressure put on Walgreens gives us a pretty good idea. Walgreens wanted to move its headquarters to Switzerland, but the U.S. Government had other plans in mind. Walgreens was threatened with an unlimited Treasury investigation (which would have been an absolute nightmare) if it were to move abroad.

It seems that flexing their muscles rather than fixing a broken tax code is how the government plans to solve this issue. There are a number of ideas for rewriting the U.S. tax code to keep businesses here and entice others back, all of which would bring back billions and billions in annual tax revenue, something a government in trillions of debt could really use.

See also The Biggest Dividend Stock Disasters of All Time.

One idea would be to install the VAT (value-added tax) system in the U.S., something that a number of foreign nations utilize. Another would be to lower the corporate tax rate to 15% or 20%, but not allow any loopholes; companies would pay that rate no matter what. The answer is likely not as simple as a few sentences and ideas once you combine corporate lobbying and a dysfunctional Congress that can’t agree on whether it is partly sunny or partly cloudy outside. Either way, it is clear that something material needs to be done. The problem is that it does not look like we are anywhere near finding a long-term solution.

The Bottom Line

Corporate inversions have been around for years, and it would appear that they are only beginning to heat up. Though the government has ideas for ways to stop major corporations overseas, the truth is that these companies can likely find a way around any kind of headache the government can create. The battle has been waging for decades and it looks like it will continue for the foreseeable future.